A Deep Dive into IPC with a Proxy-Cache Project

Introduction: The Scalability Problem

A classic scalability challenge is serving popular content to a global audience efficiently. When a major news story breaks, a web server can be overwhelmed by millions of users requesting the same article. The server spends valuable cycles reading the same files from disk repeatedly, and users far from the datacenter experience slow load times. How can we deliver content quickly without overloading the origin server?

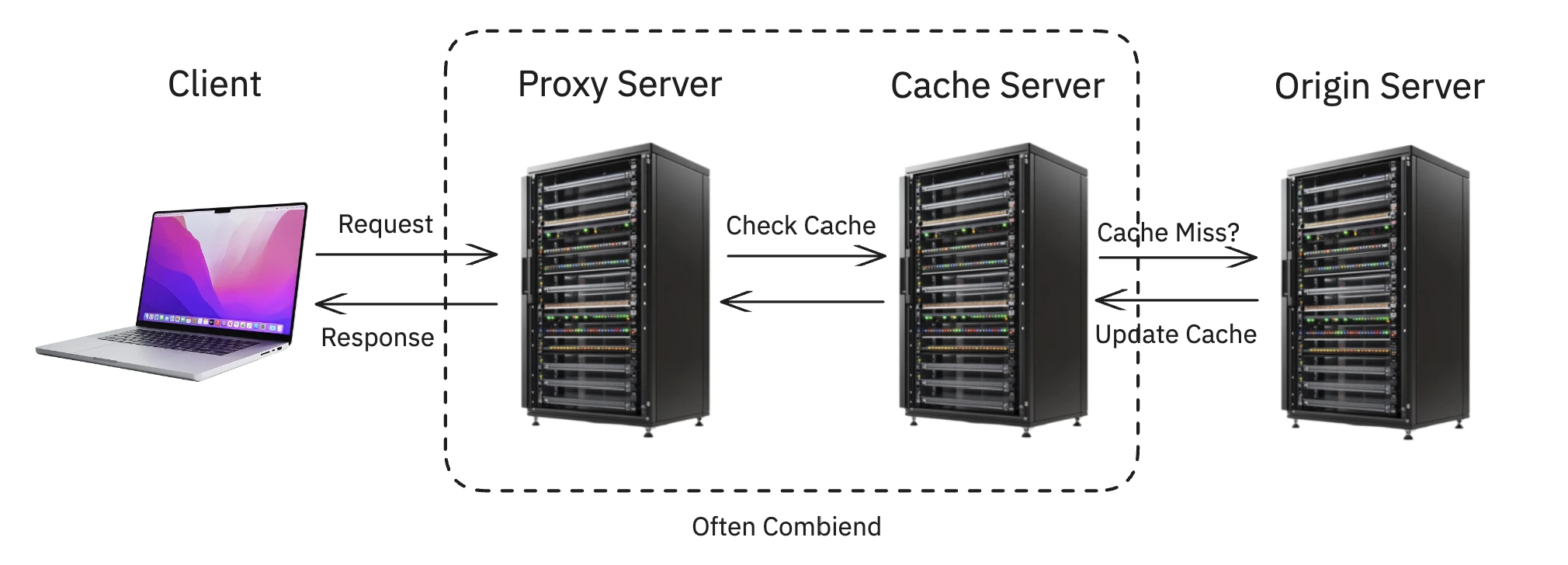

The solution involves two key architectural patterns: the cache server and the proxy server.

A cache server is based on a simple idea: it stores temporary copies of frequently requested data. Instead of the main server handling every request, the cache can serve a copy of a popular article almost instantly, often from memory. This reduces the load on the origin and provides a much faster response.

But how do client requests get directed to the cache instead of the main server? That’s where a proxy server comes in. A proxy acts as an intelligent intermediary between the client and the internet. When a request arrives, the proxy intercepts it and decides what to do. If a fresh copy is available in a nearby cache, it serves it directly. If not, it forwards the request to the main origin server, passes the response back to the client, and instructs the cache to store a copy for future requests.

In Georgia Tech’s CS 6200: Graduate Introduction to Operating Systems (GIOS), I had the opportunity to build this exact system: a cooperating proxy and cache. This project built upon the first project in the course, where I created a multithreaded client and file server. The proxy and cache processes developed in this project sit between the client and origin server, acting as an intermediary to improve performance.

This project involved two distinct processes that needed to communicate and coordinate, which required a deep dive into a fundamental topic in operating systems: Inter-Process Communication (IPC). How could I pass large amounts of file data from a cache process to a proxy process with minimal overhead? This post explores that journey and the powerful, tricky, and essential world of IPC that makes such systems possible.

This post is meant to be a showcase of the work I did on the project and the concepts I learned from it. For a broader overview of all concepts covered in the course, please see the companion post: GIOS: A Retrospective.

The Architecture: A Tale of Two Processes

In production systems, the distinction between a proxy and a cache can be blurred. For this project, their roles were intentionally separated to create a specific engineering challenge focused on IPC.

The Modern Proxy: A Versatile Gatekeeper

A proxy server acts as an intermediary between a client and a server. As Wikipedia explains, there are two main types:

- Forward Proxy: Acts on behalf of a client or a network of clients. When you use a proxy at a company or school to access the internet, you’re using a forward proxy. It can be used to enforce security policies, filter content, or mask the client’s identity.

- Reverse Proxy: Acts on behalf of a server or a pool of servers. When you connect to a major website, you’re almost certainly talking to a reverse proxy. It presents a single, unified entry point to a complex system of backend services.

Reverse proxies are fundamental to the modern web, handling several critical tasks beyond just forwarding requests:

- Load Balancing: Distributing incoming traffic across many backend servers.

- SSL Termination: Decrypting incoming HTTPS traffic so backend servers don’t have to.

- Authentication: Verifying user credentials before passing a request to a protected service.

- Caching: Storing copies of responses to speed up future requests, a role so common that the term “caching proxy” is widely used [1].

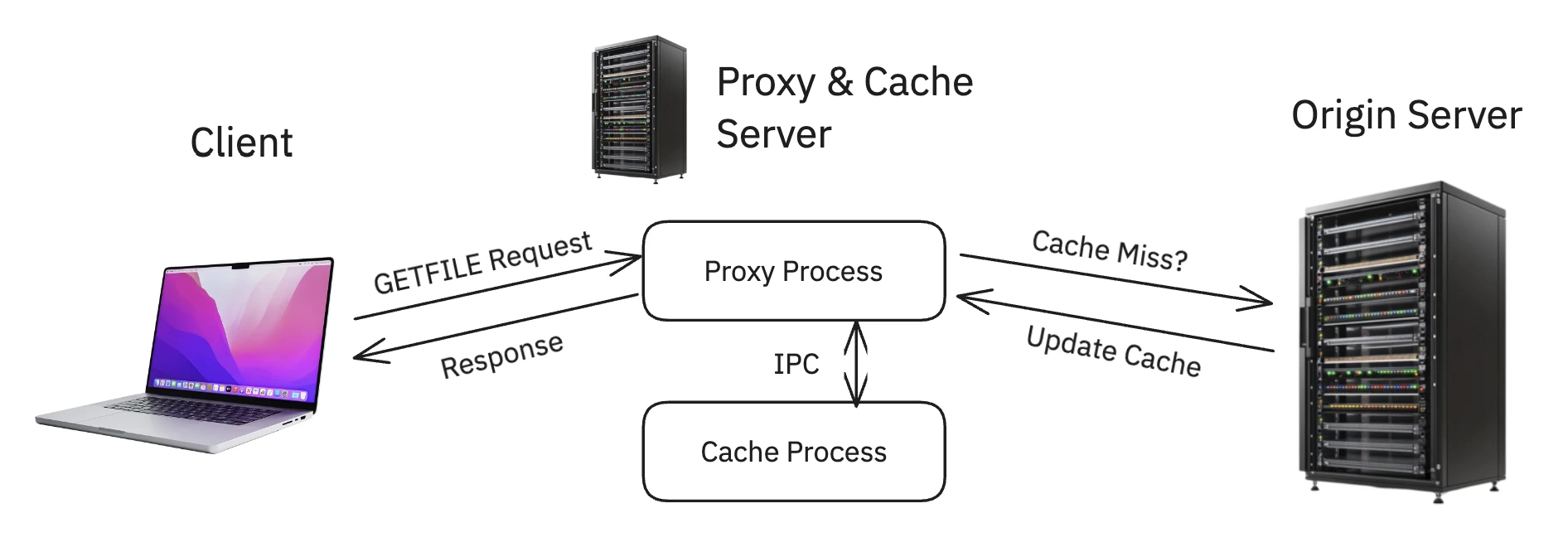

The Project’s Design: An Intentional Separation

While a production system like Nginx or a Content Delivery Network (CDN) would typically integrate proxy and cache logic into a single, highly-optimized application, this project intentionally separated them into distinct processes. This design created a focused challenge in systems programming.

- The Proxy Process: This acts as a simple reverse proxy. Its only jobs are to intercept client requests, ask the cache if it has the file, and if not, use

libcurlto fetch it from the origin server. It handles the network I/O and protocol logic. - The Cache Process: This is a pure, specialized key-value store. Its only job is to store and retrieve file data from memory. It doesn’t know about

GETFILEor HTTP; it only responds to commands from the proxy.

This separation was central to the project’s design. By splitting these tightly-coupled roles, the primary engineering problem became building a high-bandwidth, low-latency communication channel between them. This necessitated a deep dive into Inter-Process Communication, making it the core learning objective.

A Primer on Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

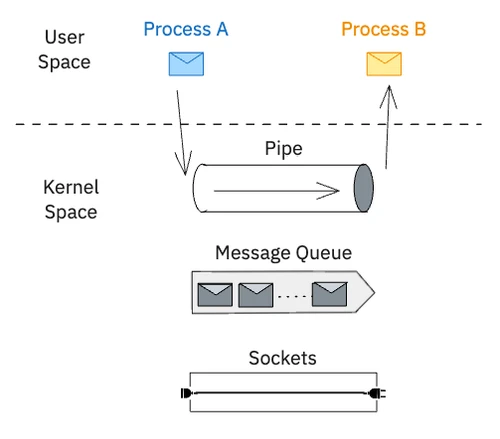

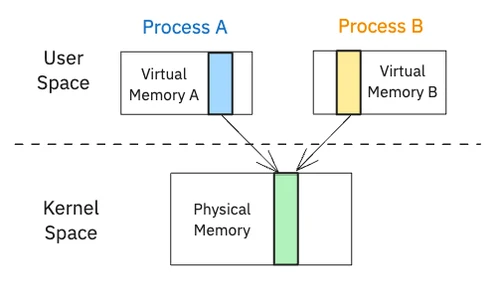

Modern operating systems are built on the principle of process isolation. Each process has its own private virtual address space, a protected memory region that other processes cannot access. This is a crucial feature for security and stability, as it prevents a bug in one application from crashing the entire system. However, this isolation presents a challenge when processes need to cooperate. To address this, the OS provides Inter-Process Communication (IPC) mechanisms, which are controlled “doorways” that allow structured and safe communication between processes.

IPC mechanisms can be broadly categorized into two families: message-based and memory-based.

- In message-based IPC, the kernel acts as a message broker. One process packages data into a message and sends it to the kernel via a system call. The kernel then delivers the message to the other process, which involves another system call. This process requires copying the data from the sender’s virtual memory to the kernel and then from the kernel to the receiver’s virtual memory. While this approach is safe and structured, the overhead from kernel involvement and data copying can be significant. Common examples include Pipes for simple byte streams, Message Queues for structured messages, and Sockets for network communication.

- In memory-based IPC, the kernel’s role is to set up a shared environment. It designates a specific region of physical RAM and maps it into the address spaces of multiple processes. Once this Shared Memory region is established, the kernel steps aside, and processes can read and write to it directly at memory speed, without system calls or data copying. This offers exceptional performance but introduces a significant risk: without proper coordination, processes can interfere with each other, leading to data corruption.

This risk highlights the need for synchronization primitives. When using shared memory, it’s essential to control access to prevent race conditions. Semaphores are a classic tool for this purpose, acting as a traffic light to ensure that only one process can access the shared “intersection” at a time. They don’t transfer data themselves but make it safe for other mechanisms to do so.

For this project, the goal was maximum performance, which led to a hybrid approach: Shared Memory for transferring large file data and a Message Queue for coordination.

The project mandated a strict division of this communication:

- A high-speed data channel for transferring the large file contents.

- A separate command channel for control messages like “do you have this file?”

Message Queues: The Command Channel

If shared memory is the bulk cargo freighter, the message queue is the dispatch radio used to coordinate. While shared memory is just a raw slab of bytes, message queues are for sending small, discrete, structured messages. The modern POSIX API for message queues is often preferred for its simplicity and file-descriptor-based approach.

With the POSIX API (mq_open, mq_send, mq_receive), message queues are identified by a simple name (e.g., /my_queue_name). Instead of a message “type,” POSIX queues use a message priority. This allows a process to send urgent commands that can be read from the queue before older, lower-priority messages.

This makes them ideal for a command channel, where a process might need to listen for and respond to different kinds of requests. Here is a generic example of the API in use:

// In the sender:

// 1. Open a named queue

mqd_t mq = mq_open("/my_queue_name", O_WRONLY);

// 2. Send a message with a specific priority

mq_send(mq, "your_message", strlen("your_message"), 10);

// In the receiver:

// 1. Open the same queue for reading

mqd_t mq_recv = mq_open("/my_queue_name", O_RDONLY);

// 2. Receive the message

char buf[8192];

unsigned int sender_prio;

mq_receive(mq_recv, buf, 8192, &sender_prio);The kernel handles all the buffering and synchronization of the queue itself, making it a reliable—if slower—communication channel perfectly suited for control signals.

Shared Memory: The High-Speed Data Link

Shared memory is the IPC equivalent of teleportation. To make it work, one process first needs to request a new segment from the OS using a system call like shmget() (from the classic System V API) or shm_open() (from the more modern POSIX API). The OS reserves a chunk of physical memory and provides a unique key or name to identify it.

Next, any process wanting to use this segment—including the creator—must “attach” it to its own virtual address space using a call like shmat(). The OS performs its page table magic, and the process gets back a simple void* pointer. From that moment on, it’s just memory. There are no special write_to_shared_memory() calls. A process can use memcpy, pointer arithmetic, or direct assignments on that pointer, and the changes are instantly visible to any other process attached to that same segment because they all point to the same physical RAM.

The POSIX equivalent achieves the same result by treating the shared memory segment like a file descriptor that can be memory-mapped:

// 1. Create a named shared memory object

int fd = shm_open("/my_shm_key", O_CREAT | O_RDWR, 0666);

// 2. Set its size

ftruncate(fd, sizeof(struct shared_data_struct));

// 3. Memory-map it to get a pointer

void *ptr = mmap(0, sizeof(struct shared_data_struct), PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);This raw pointer access is the source of both its power and its danger.

- No Built-in Synchronization: The pointer is just a

void*; it carries no information about whether another process is currently writing to that memory. If the cache is in the middle of amemcpyto the shared segment while the proxy tries to read from it, the proxy will get a corrupted, half-written file. - Life After Death: That memory segment is owned by the kernel, not the process. If a program crashes without explicitly detaching and telling the OS to destroy the segment, it becomes “orphaned”—invisible to new processes but still consuming system resources until the next reboot. This makes rigorous cleanup and signal handling an absolute necessity.

Preventing Chaos with Semaphores

Using shared memory requires more than just preventing two processes from writing at the same time; it requires coordinating a handoff. How does the proxy (the “reader”) know when the cache (the “writer”) has finished placing a new file into shared memory? How does the cache know when the proxy is done reading, so it’s safe to overwrite the memory with new data? This is a classic producer-consumer problem.

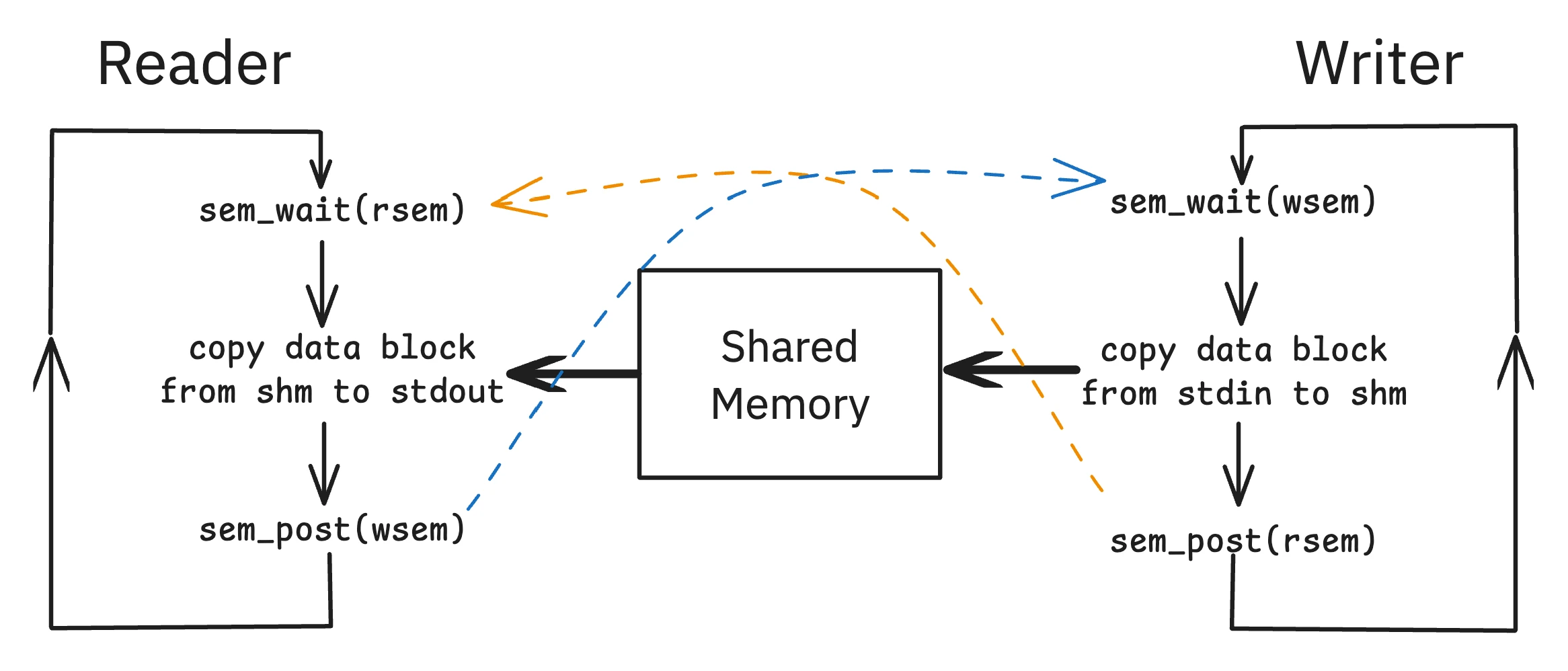

One approach is to use a pair of semaphores to act as traffic signals.

wsem(Write Semaphore): This semaphore can be thought of as representing the number of “empty” slots available for the writer to write into. It’s initialized to 1. The writer must wait on this semaphore before it can write.rsem(Read Semaphore): This represents the number of “full” slots ready for the reader to read. It’s initialized to 0, because initially, there is no data to read.

This creates a clean, synchronized dance:

- The writer first calls

sem_wait(wsem). Since it was initialized to 1, this succeeds immediately, and it now “owns” the shared buffer. - It copies the file data into the shared memory segment.

- It then calls

sem_post(rsem), signaling to the reader that a file is ready. - The reader, which was likely blocked on

sem_wait(rsem)(since it started at 0), now unblocks and can safely read the data. - After reading, the reader calls

sem_post(wsem), signaling that the shared buffer is now empty and available for the writer to write the next file.

This two-semaphore system elegantly ensures that the reader never reads an incomplete file and the writer never overwrites a file before the reader has had a chance to read it.

Semaphores are just one of many tools for synchronization. For a broader look at how they compare to thread-focused tools like mutexes or high-performance spinlocks, see my overview of Synchronization Constructs in the GIOS Retrospective.

Design in Practice: Synchronization and Robustness

With the core components defined, the real challenge was making them work together reliably. This involved not just preventing data corruption but also designing the system to handle the realities of process lifecycles and startup.

The Coordination Challenge

With a message queue for commands, shared memory for bulk data, and semaphores for synchronization, the next step was to weave them into a coherent protocol. This is where the core design challenge lay. It’s not enough to have the right tools; they must be orchestrated correctly.

This raised several critical design questions:

- When the proxy receives a “file is ready” message, how does it know where in the shared memory segment to look for the data?

- How does the cache know which part of the shared memory is free to use for a new file it just fetched?

- Is it better to have one single, large shared memory segment that is partitioned and managed, or to create and destroy smaller segments on demand?

- How are the semaphores associated with the specific data they are protecting?

Answering these questions was the heart of the engineering task. There are many valid patterns one could use to build a robust solution, each with different trade-offs in complexity and performance. The key is to create a clear, unambiguous system of rules that both processes can follow to communicate without error.

Getting these details right was the most challenging and rewarding part of the project.

Responsibility and Resource Management

A key design decision mandated by the project was that the proxy would be responsible for creating and destroying all IPC resources. From the cache’s perspective, this design respects its memory boundaries. It makes the cache a more robust service, capable of handling multiple proxy clients without being brought down by a single misbehaving one. If a proxy crashes, it’s responsible for its own mess, and the cache can continue serving other clients.

This responsibility extends to cleanup. It’s not enough for the system to work; it must also exit cleanly. The project required implementing signal handlers to catch termination signals like SIGINT (from Ctrl-C) and SIGTERM (from a kill command). When caught, these signals trigger a cleanup routine that meticulously removes all shared memory segments and message queues before the process terminates, preventing orphaned resources from littering the OS.

Flexible Startup

Finally, the system had to be robust to the order in which the processes were started. The proxy could launch before the cache was ready, or vice-versa. This meant the connection logic couldn’t be a one-time attempt. The proxy, upon starting, had to be prepared to repeatedly attempt a connection to the cache’s command channel if it wasn’t yet available. This small detail is a classic example of the kind of defensive programming required when building distributed or multi-process systems.

Conclusion: Lessons from Building a Cooperative System

This project was a fantastic lesson in the trade-offs of system design. While building a single, monolithic program is often simpler, splitting a system into specialized processes can lead to a more modular, scalable, and maintainable architecture.

The key takeaways were:

- IPC is a spectrum: There’s a tool for every job, from slow-but-simple pipes to fast-but-complex shared memory. The right choice depends entirely on the problem’s requirements.

- Synchronization is non-negotiable: With great power comes great responsibility. Using high-performance IPC like shared memory requires robust, process-aware synchronization to prevent chaos.

- Resource management is paramount: Processes are mortal, but OS-level resources can be eternal. Writing code that cleans up after itself is a hallmark of a reliable system.

While a production cache might use more advanced techniques, the fundamental principles are the same. This project provided a tangible, low-level understanding of how independent programs can be orchestrated to build a cooperative, high-performance system.

Additional resources

These books and guides were extremely helpful for understanding the concepts and APIs for IPC in C.

The C Programming Language

Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie

The definitive book on C, written by its creators. Essential for mastering the language itself.

Beej's Guides to C, Network Programming, and IPC

Brian 'Beej' Hall

An invaluable, practical, and free resource. The IPC guide was a lifesaver for this project, providing clear, working examples for shared memory and semaphores.

The Linux Programming Interface

Michael Kerrisk

The encyclopedic guide to the Linux and UNIX system programming interface. The chapters on System V IPC and POSIX IPC are incredibly detailed and authoritative.

Operating System Concepts 10th Edition

Silberschatz, Galvin, and Gagne

This book was a great resource for understanding the concepts of IPC and synchronization.

In accordance with Georgia Tech’s academic integrity policy and the license for course materials, the source code for this project is kept in a private repository. I believe passionately in sharing knowledge, but I also firmly respect the university’s policies. This document follows Dean Joyner’s advice on sharing projects with a focus not on any particular solution and instead on an abstract overview of the problem and the underlying concepts I learned.

I would be delighted to discuss the implementation details, architecture, or specific code sections in an interview. Please feel free to reach out to request private access to the repository.