Building a Scalable Multithreaded File Server in C

Introduction: The Challenge

Ever wondered what really happens when you click a download link? It seems like magic. You click, and a file appears. But behind that simple action lies a carefully orchestrated conversation between computers, a conversation refereed by their operating systems. For my first project in Georgia Tech’s CS 6200: Graduate Introduction to Operating Systems (GIOS), I had to build both sides of that conversation: a multithreaded file server and client, from scratch, in C.

The goal was to build a complete system: a server capable of handling multiple file requests simultaneously and a client that could download multiple files concurrently. This wasn’t just about writing code; it was about a head-first dive into the core concepts that make the modern internet possible: network sockets, system calls, concurrency, and protocol design.

Going in, I was comfortable with C’s syntax but had never touched the Berkeley socket API. Networking was a black box I’d only ever interacted with through convenient abstractions like Python’s requests library. This project was my chance to pry open that box. In this post, I want to walk you through that journey—not just what I built, but the fundamental whys behind the code and the lessons learned along the way.

This post is meant to be a showcase of the work I did on the project and the concepts I learned from it. For a broader overview of all concepts covered in the course, please see the companion post: GIOS: A Retrospective.

The Foundation: Client-Server & Network Models

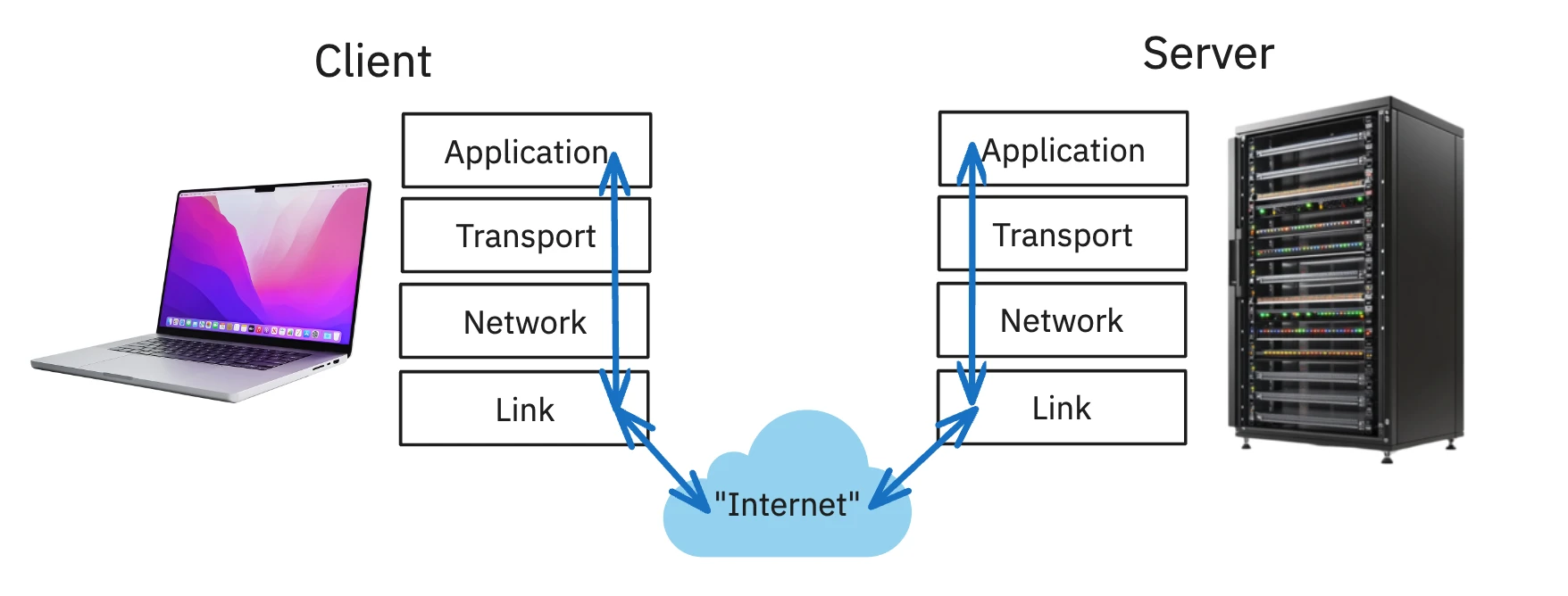

At its heart, network communication is a conversation. The most common pattern for this conversation is the client-server model. It’s a simple idea: a client (like your web browser) needs something, and a server (like the computer hosting google.com) has something to provide. The client initiates the conversation, and the server responds.

But for this conversation to work, both sides need to speak the same language and follow the same rules. The TCP/IP model provides this rulebook. It’s a 4-layer stack, and for this project, we’re mostly concerned with two:

- Application Layer: This is where our custom application logic lives. We define the meaning of the conversation. For web browsers, this is HTTP (

GET /index.html...). - Transport Layer: This layer is responsible for the reliability of the connection. We primarily use the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). For sending a file, TCP is the perfect choice. It’s connection-oriented (the client and server maintain a connection for the duration of the transfer) and reliable (it guarantees that all the bytes you send will arrive at the destination, and in the correct order). The alternative, UDP, is faster but “fire-and-forget”—not ideal when you can’t afford to lose a single byte of your file.

The Operating System handles the lower layers (Network and Link), managing the messy details of IP addresses and routing data across the physical network. Our application code, thankfully, doesn’t have to worry about that. Instead, it talks to the Transport Layer through an interface provided by the OS: a socket.

Sockets: The OS Gateway to the Network

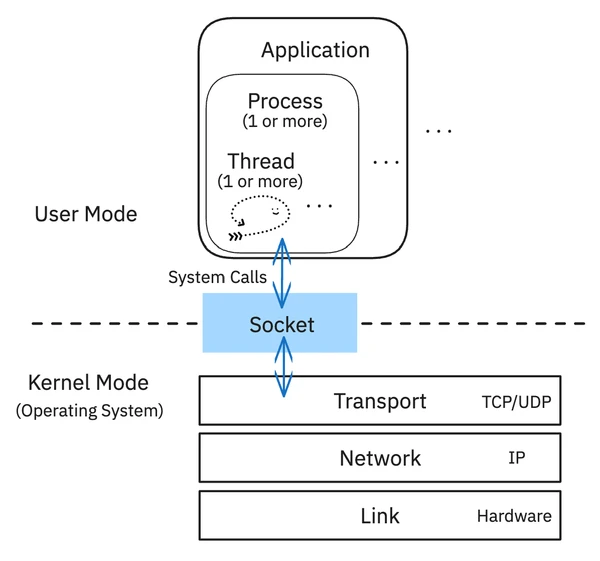

A socket is one of the most powerful abstractions in modern computing. It’s a special kind of file descriptor that represents a connection endpoint. Think of it like a phone jack in the wall. As an application developer, you don’t need to know about the complex wiring inside the wall (the TCP/IP stack, the network card drivers); you just need to know how to plug your “phone” into the jack to start a conversation.

This abstraction is necessary because network hardware is a protected resource. Your user-level application can’t just write bytes to the network card directly. That would be chaos. Instead, you have to ask the OS to do it for you. This is accomplished via system calls.

When your program calls a function like send(), it’s not an ordinary function call. It’s a request to the OS kernel. The CPU switches from User Mode to Kernel Mode, a privileged state where it has full access to the hardware. The kernel takes your data, breaks it into packets, adds the necessary TCP/IP headers, and sends it to the network card. This user/kernel separation is a fundamental security and stability feature of all modern operating systems, and seeing it in action makes the theory tangible.

The Socket API in Action (C)

The API for using sockets is direct and explicit. Here’s a conceptual overview of the key API calls for a simple server and client. This simple example follows Beej’s Guide to Network Programming, which was a great resource for this project.

Server Lifecycle:

// 1. Create the socket

int server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

// 2. Bind the socket to an address and port

struct sockaddr_in address;

// ... setup address struct ...

bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address, sizeof(address));

// 3. Listen for incoming connections

listen(server_fd, 5); // 5 is the backlog size

// 4. Accept a new connection (this blocks until a client connects)

int client_fd = accept(server_fd, NULL, NULL);

// 5. Communicate with the client

char buffer[1024] = {0};

recv(client_fd, buffer, 1024, 0);

send(client_fd, "Hello from server", 16, 0);

// 6. Close the connection

close(client_fd);Client Lifecycle:

// 1. Create the socket

int client_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

// 2. Specify server address to connect to

struct sockaddr_in serv_addr;

// ... setup server address struct ...

// 3. Connect to the server

connect(client_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&serv_addr, sizeof(serv_addr));

// 4. Communicate

send(client_fd, "Hello from client", 16, 0);

recv(client_fd, buffer, 1024, 0);

// 5. Close the connection

close(client_fd);The server’s flow is more complex because it has a “listening” socket that acts as a factory, creating a new socket for each client connection it accepts.

The GETFILE Protocol

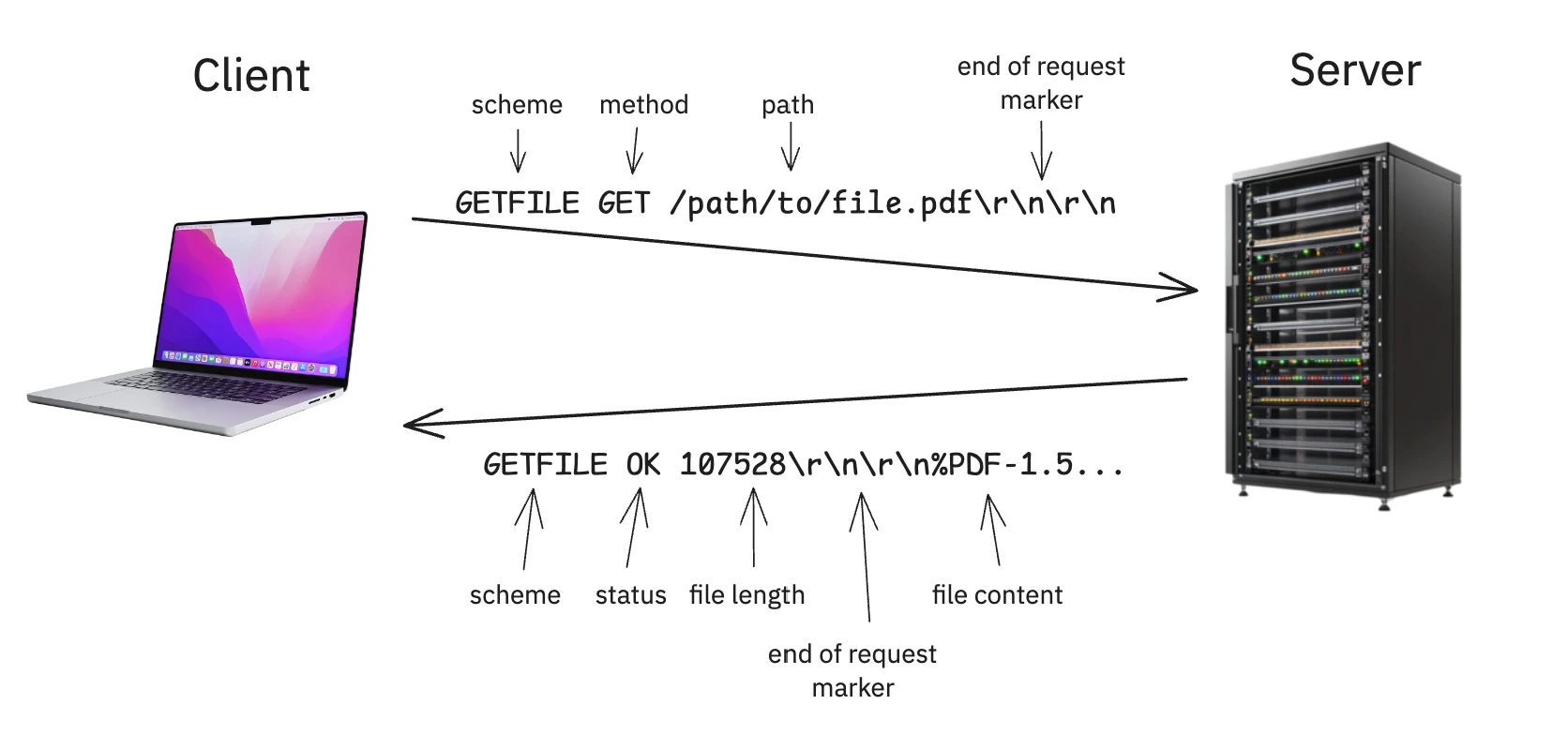

With the ability to send and receive bytes, I needed to give those bytes meaning. I implemented a simple HTTP-like protocol called GETFILE, which was specified in the project. Working with a bespoke protocol, no matter how simple, is a fantastic exercise. It forces you to think about ambiguity, parsing, and error handling with raw byte streams.

The protocol specification from the project is strict and resembles a simplified version of HTTP/1.0.

Expand to see more details about the GETFILE protocol including the client request, server response, and error handling:

Client Request

The client sends a single request header, terminated by a \r\n\r\n sequence.

GETFILE GET /<path>\r\n\r\n- Scheme: Always

GETFILE. - Method: Always

GET. - Path: The path to the requested file, which must begin with a

/. - Terminator: A specific four-byte sequence: carriage return, newline, carriage return, newline. This marks the end of the header.

Server Response

The server’s response also consists of a header, and if successful, a body.

A successful response looks like this:

GETFILE OK <length>\r\n\r\n<content>- Scheme: Always

GETFILE. - Status:

OKfor a successful request. - Length: The size of the file in bytes, represented as an ASCII string.

- Header Terminator: The

\r\n\r\nsequence separates the header from the file’s content. - Content: The raw bytes of the file. The client must read exactly

lengthbytes from the socket.

Handling Errors

A robust protocol must clearly define its error states. GETFILE has three:

FILE_NOT_FOUND: The request was valid, but the file doesn’t exist on the server.INVALID: The client sent a malformed request (e.g., wrong scheme, missing spaces, incomplete header).ERROR: An unexpected error occurred on the server side (e.g., could not read the file due to permissions).

For any of these statuses, the server sends a single header line with no body content:

GETFILE <status>\r\n\r\nFor example: GETFILE FILE_NOT_FOUND\r\n\r\n.

A Note on C Strings

A crucial and challenging part of implementing this in C is that the received data is not null-terminated. A buffer from recv() is just a sequence of bytes. You cannot use standard string functions like strcpy or strstr on it directly without risking reading past the buffer’s boundary. Parsing requires careful, manual inspection of the bytes, searching for the spaces and the final \r\n\r\n sequence. This was a fantastic, if sometimes frustrating, lesson in the difference between a C “string” and a raw byte array.

Scaling Up with Concurrent Design: The Boss/Worker Pattern

A single-threaded application, whether a client or a server, can only do one thing at a time. A server could only handle one download at once, and a client could only request one file at a time. This is a major bottleneck. To build a system that could handle significant load—many simultaneous file requests—both the client and server for this project needed to be multithreaded.

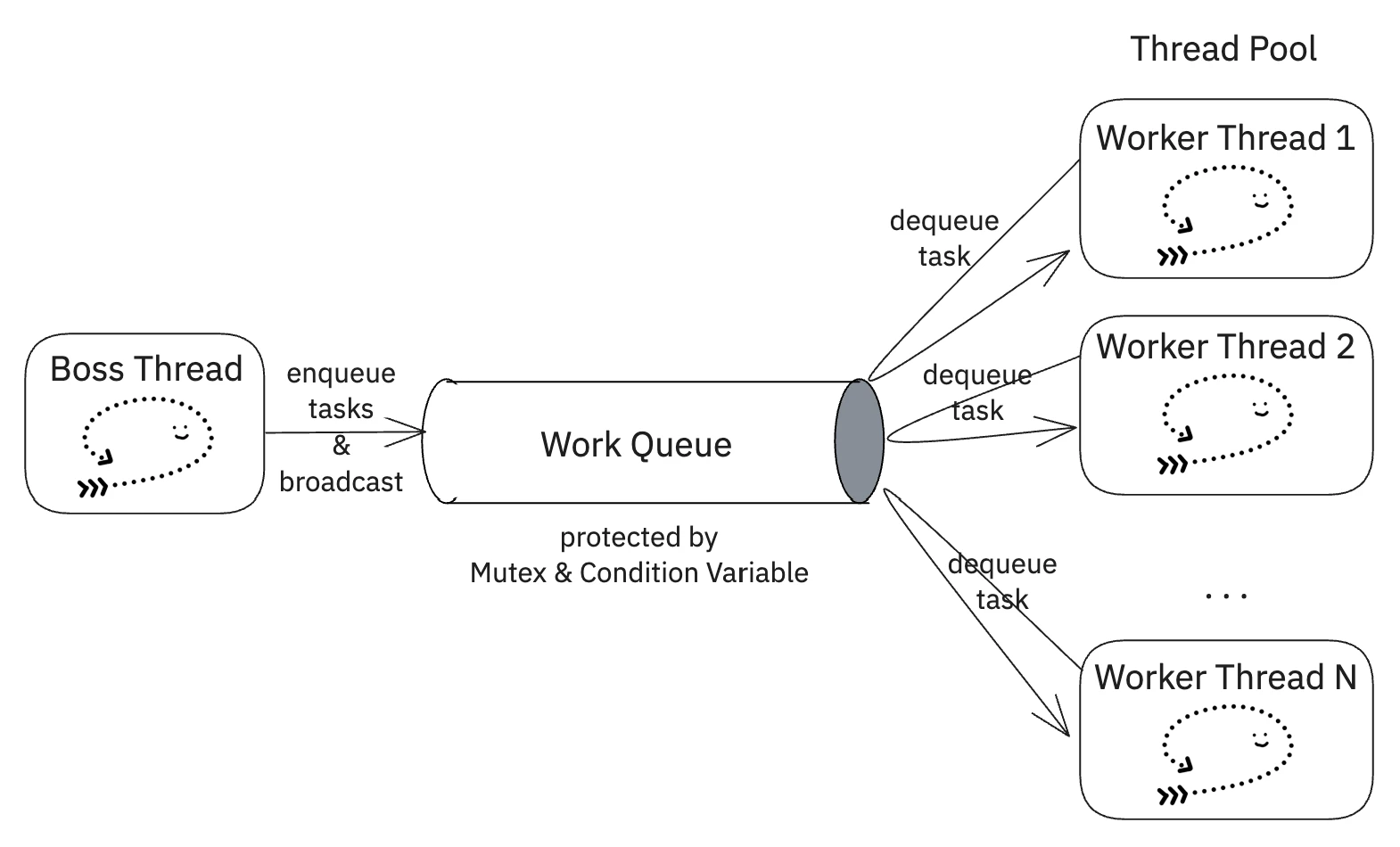

The design pattern used to achieve this was the Boss/Worker model, a powerful and common strategy for structuring concurrent applications.

The pattern has two main components:

- The Boss Thread: Its sole responsibility is to accept incoming work and place it into a shared queue. It doesn’t perform the work itself. This makes it highly responsive and prevents it from becoming a bottleneck.

- Worker Threads: A pool of one or more worker threads waits for work to appear in the queue. When a task is available, a worker takes it, processes it to completion, and then returns to the queue to wait for another task.

This decouples the act of receiving a request from the work of processing it, allowing the system’s throughput to be scaled by simply adjusting the number of worker threads. There’s a certain elegance to seeing it in action: the boss thread, laser-focused on one task, feeding a pool of workers that spring to life as jobs arrive. It’s a beautiful, efficient division of labor.

An important performance characteristic of this pattern is that the overall system throughput is fundamentally limited by the boss thread’s processing speed. Since the boss must handle every incoming request, the maximum request rate the system can sustain is approximately 1/boss_processing_time. The worker threads determine how many requests can be processed concurrently, but they can’t process requests faster than the boss can accept them.

This pattern was applied to both sides of our file transfer application:

- On the Server: The Boss thread’s only job was to

accept()new client connections. It would immediately place the new client socket descriptor into the work queue. The Worker threads would then pull from this queue, each handling a fullGETFILEtransaction with a single client before going back for more work. - On the Client: The pattern was mirrored. The Boss thread was responsible for parsing the list of files to download and enqueuing a request for each. The Worker threads would each take a request, connect to the server, download the file, and then look for the next download job.

This model is powerful, but it introduces the classic challenges of concurrency.

The Danger Zone: Concurrency, Mutexes, and Condition Variables

The work queue is shared state. If the Boss thread tries to add to the queue at the same time a Worker is trying to remove from it, you get a race condition that can corrupt the queue’s state, leading to crashes or bizarre bugs.

To solve this, you must protect the shared data structure. The project required using two key synchronization primitives from the pthreads library:

-

Mutexes (

pthread_mutex_t): A mutex (short for mutual exclusion) acts as a lock. Before accessing the queue (the critical section), a thread must acquire the lock. If another thread already holds it, the thread will block until the lock is released. This ensures only one thread can modify the queue at a time. -

Condition Variables (

pthread_cond_t): But what should a worker do if it locks the queue and finds it’s empty? It could unlock and then immediately try to lock again in a tight loop. This “busy-waiting” burns CPU cycles for no reason. A much more elegant solution is a condition variable. It allows threads to sleep efficiently until there’s a reason to wake up. When the boss thread adds a new job to the queue, it ‘broadcasts’ a signal to all worker threads to wake up and check the queue.

Building and Testing

A C project of this complexity demands proper tooling for building and testing.

-

Environment: The project had specific Linux dependencies, so I used Docker to create a consistent, reproducible virtual machine, mirroring the official testing environment. This saved me from countless “works on my machine” headaches.

-

Build System: You can’t just run

gccover and over. AMakefileis essential for any serious C project. It automates the tedious process of compiling, linking, and cleaning up object files. More importantly, it serves as a canonical place to define compiler flags like-Wall(turn on all warnings),-g(include debugging symbols forgdb), and-pthread(link the pthreads library). -

Automated and Stress Testing: How do you prove your concurrent server really works? You write tests—and not just simple ones. I took two approaches here that were critical to my success.

To push the server to its limits, I used the multithreaded C client itself as a stress-testing tool. By configuring it to request dozens of files concurrently, I could simulate real-world load, uncovering subtle race conditions or deadlocks in the server. I also played with

valgrindto check for memory leaks and invalid memory accesses, which is essential in C projects—especially when handling many threads and dynamic buffers. These tools together gave me confidence that my server was not only correct, but also robust and leak-free under heavy use.

Here’s a small generic pytest example of using the socket library to test a server (not specific to the GETFILE protocol to avoid academic integrity issues):

import socket

# Assumes the C server is running on localhost:8888

SERVER_ADDR = ("localhost", 8888)

def test_get_file_success():

"""Tests a successful file download."""

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.connect(SERVER_ADDR)

s.sendall(b"GET existent_file.txt\n")

# Read the 'OK <size>\n' header

header = s.recv(1024).split(b'\n')[0]

parts = header.split(b' ')

assert parts[0] == b"OK"

size = int(parts[1])

# Read the file content

data = s.recv(size)

assert len(data) == size

# Could also assert file content matches a local copy

def test_get_file_not_found():

"""Tests the server's response for a non-existent file."""

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.connect(SERVER_ADDR)

s.sendall(b"GET non_existent_file.txt\n")

response = s.recv(1024)

assert response.strip() == b"ERROR 1"Conclusion: From Theory to Practice

This project served as a practical application of fundamental operating systems concepts, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world implementation. It provided a low-level look into the layered, cooperative systems that underpin modern network technology.

The key technical takeaways include:

- The Power of OS Abstractions: Sockets and threads are powerful, time-tested abstractions that enable the development of complex network applications without managing low-level hardware details.

- The Challenges of Concurrency: While multithreading improves throughput, it introduces significant complexity. Correct synchronization using mechanisms like mutexes and condition variables is not optional; it is a requirement for correctness and stability.

- The Central Role of Protocols: The foundation of any network service is a clear, unambiguous, and strictly-defined protocol.

- The Necessity of External Testing: A robust test suite that acts as a true client is the most effective way to validate protocol compliance, handle edge cases, and ensure system reliability under load.

The patterns I used here—thread pools, work queues, custom protocols—are the building blocks for the massive, distributed systems we use every day. While a production web server like Nginx uses far more advanced techniques (like event-driven I/O with epoll or kqueue), the fundamental goal remains the same: handle as many concurrent clients as possible, as efficiently as possible. This project provided a tangible, low-level look at how that goal is achieved, connecting the high-level “magic” of a network request to the concrete logic of a send() system call.

Additional resources

The man pages for the socket and pthread libraries were invaluable for this project.

man socket

man pthread

man pthread_mutex_t

man pthread_cond_t

...etcOr online:

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/socket.2.html

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/pthread.3.html

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/pthread_mutex_t.3.html

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/pthread_cond_t.3.html

These books were also extremely helpful:

The C Programming Language

Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie

The definitive book on C, written by its creators. I ready this cover to cover before the course started to brush up on my C knowledge.

Beej's Guides to C, Network Programming, and IPC

Brian 'Beej' Hall

An invaluable, practical, and free resource for C programming, socket programming, and inter-process communication. The network programming guide was especially helpful for this project.

The Linux Programming Interface

Michael Kerrisk

This is structured as an encyclopedic guide to the Linux and UNIX system programming interface. The chapters on sockets and threads were particularly helpful for this project.

Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces

Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau and Andrea C. Arpaci-Dusseau

This is the main book I used to supplement the lectures. It’s filled with easy-to-understand explanations of complex topics and covers most of the material in the course. I highly recommend it.

In accordance with Georgia Tech’s academic integrity policy and the license for course materials, the source code for this project is kept in a private repository. I believe passionately in sharing knowledge, but I also firmly respect the university’s policies. This document follows Dean Joyner’s advice on sharing projects.

I would be delighted to discuss the implementation details, architecture, or specific code sections in an interview. Please feel free to reach out to request private access to the repository.